The fifth-century Greek historian Herodotus relates that the Etruscans left Asia Minor by sea and, after wandering around for some time, ended up in Italy. Its opponents maintain that Etruscan culture developed in Italy while at the same time absorbing influences from abroad. In Etruscan art various elements can be recognized which were definitely borrowed from other cultures, while many distinctly Etruscan features are equally evident. With their colonies in southern Italy, the Greeks exerted particular influence.

City-states

The Etruscans lived in central Italy between Florence and Rome, that is, between the rivers Arno and Tiber. Etruria never truly formed a unified country or a politically coherent region, however. Like the Greeks, they were governed by city-states which functioned relatively independently. The 12 most important formed a federation which met once a year: Veii, Cervetri, Tarquinia, Vulci, Orvieto, Roselle, Vetulonia, Populonia, Chiusi, Perugia, Arezzo, Volterra.

Language

Long Etruscan texts have not come down to us, so we know little about the language. Most of our knowledge is based on more than 13,000 short messages, nearly all of which consist of inscriptions on objects. Etruscan writing reads from right to left and, being derived from the Greek alphabet, can quite easily be transliterated. But of only 200 words the meanings have yet been established, many of which are proper names inscribed on cinerary urns and bronze objects, like the deceased Arnth (first name) Carpnate (family name), son of (the woman) Catnei (APM01510).

Religion

Fortunately, we have some texts about the Etruscans written by non-Etruscans. Many of them concern religious matters and spiritual life.. Religious laws and regulations were very carefully observed. An augur was a priest especially gifted in the understanding of the gods' intentions, which he could recognize in the configurations of birds. An augur was inseparable from his lituus, a curved staff which identified his profession and conferred status. When a flock of birds flew into view, he read divine messages in their direction and pattern of flight.

Villanovan period

The earliest phase of Etruscan culture, about 900-675 B.C., is named 'Villanovan' after the small town of Villanova in the vicinity of Bologna where, in the nineteenth century, the first remains of the period were discovered. The economy centred mainly on agriculture in combination with a small amount of trade.

Burials have yielded the most characteristic artefacts, made mostly of clay and bronze. The different types of bronze clasps or fibulae, resembling safety pins, are named after their different forms, for example, disc, snake and bloodsucker fibulae.

Cinerary urns

With their conical bowls and lids, the so-called biconical ash urns are also typically Villanovan (APM11000). They were not shaped on a potter's wheel but built up by hand from rather rough, unpurified clay which fired grey, brown or deep black. The final product is today referred to as impasto. The decorative lines were incised when the clay was still moist. With helmet-shaped lid, an urn probably held a warrior's ashes. The same kind of clay and shaping technique were used to manufacture cups, beakers and bowls. Their small geometric ornaments, consisting of rings and rectangles, are noteworthy.

Graves in the fields around Chiusi contained cinerary urns with lids in the shape of stylized human heads. They date from the end of the seventh century and are called 'canopic' after an Egyptian type of jar. The faces are not true portraits but rather standardized depictions. To gain some sense of realism, the canopic urns were probably painted and their now bare heads originally covered with wigs of human hair.

Eastern influences

During the seventh century B.C. the Etruscans maintained contacts with many peoples of the eastern Mediterranean. Their chief motive was trade and, as a result, they assimilated many eastern influences. Described therefore as orientalizing, the period 700-600 B.C. is marked by, among other things, depictions of exotic animals like the three-headed snake which fights a woman.

Bucchero pottery

It is said of the Etruscans that they ate twice a day, well and profusely. The lustrous black pottery called bucchero typifies their material culture in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. It was used for pouring and drinking wine. Early wheel-turned bucchero dating from the second half of the seventh century is thin-walled and has a shiny, deep black surface. The solid black colour results from the low temperature and smoky atmosphere in which the pottery was fired. Most probably, bucchero developed as an improved form of the earlier rough impasto. It often appears to imitate metalware. A few decades later, bucchero became less refined as the thickness of the wall increased and the colour grew greyer. Bucchero's fan-shaped ornaments are particularly striking: they were pressed with a comb into the leather hard clay. Other motifs were made with a cylinder stamp which was rolled over the moist surface.

Politics and trade

The mining of metal ore and the manufacture of bronze in particular played a big part not only in the economy but also in Etruscan social and cultural life. Archaeological finds from various places show that the mines of Etruria yielded iron, copper, lead, tin and silver which were worked into diverse products and exported over a wide area. Without this metal, which was got under horrible working conditions, the Etruscan economy could hardly have been so successful. In the first century A.D., Pliny the Elder wrote in his Naturalis Historia (XXXIII, 70) about the mine pits and the techniques with which the Etruscans extracted metal ore. Specialized bronze smiths found ample employment in Etruria because their products were in great demand. Not only bronze pins, clasps and belts, but also bronze vessels have turned up in graves, testifying to moments of inventive creativity in combination with a high general level of craftsmanship. A spectacular example is a bronze kantharos which weighs 200 grams only! It consists of sheets of hammered bronze which were nailed together.

Etruscan women

Etruscan women enjoyed a higher social position than Greek ones. Judging from the funerary gifts and the representations of women in chamber graves, we can cautiously conclude women were not entirely limited to playing a subordinate role. Etruscan craftsmen were famous for the bronze mirrors they made for women. The reflecting surface is highly polished and the opposite side often embellished with skilfully rendered mythological scenes.

Temples

Like the Greeks, the Etruscans regarded a temple as the house of the god to whom it was dedicated, although their actual temples differed from those of the Greeks. As the majority of these sacred buildings, which are known to have been in Veii, Orvieto and Pyrgi, were constructed of wood, they have largely or completely perished. Clay models of Etruscan temples furnish us with indispensible information. They were offered as ex-votos and discovered buried in pits near sanctuaries which archaeologists have excavated. Curiously, none of the models shows the stairs which led up the podium on which the temple stood.

Antefixes

The dating of Etruscan temples depends on stylistic analyses of their terracotta ornaments. The roof was covered with terracotta tiles, and sometimes terracotta statues stood on the ridgepole. The flat tiles were linked to each other by curving ones. Along the eave, the opening of each semicircular tile was closed off with a so-called antefix, which was very often colourfully painted, like the woman's head. The mysterious expression on her lips is known as an 'archaic smile'. The so-called archaic Ionian style of the face refers to the influence of sixth-century artisans who emigrated from the western coast of Asia Minor to Etruria. Features of this style are the oval head and the almond-shaped eyes.

Votive offerings

The practice of giving votives to the gods was commonplace in Etruria. In this way, an Etruscan tried to come directly into contact with a god or at least to gain a god's favour. Huge numbers of such offerings have come to light during excavations. Their forms greatly vary, ranging from bronze statuettes of warriors or gods to small clay portrayals of animals. Many museum collections preserve terracotta representations of parts of human bodies which the Etruscans dedicated to the gods in the hope of being healed. Hundreds of such anatomical images have been unearthed around the sanctuaries of gods who directly influenced mankind's health.

Life after death

The Etruscans believed strongly in the continuation of life after death. The deceased was escorted to the grave and the underworld with much care. A grave-side meal was part of the burial ceremony. Many graves have yielded the eating and drinking services used at these meals. The practice of roasting meat and preparing dishes over burning charcoal in braziers might be regarded as a precursor of the present-day barbecue.

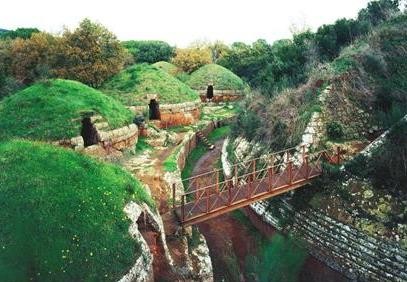

Cremation and inhumation

In the classical and Hellenistic periods the Etruscans both cremated and buried their dead. As Etruscan towns have nearly entirely vanished, Etruscan funerary architecture is all the more conspicuous. Many graves in major necropolises, as at Tarquinia, are decorated with murals which have been well conserved. The dead were laid either in niches or on couches carved out of the stone walls. Some underground chamber graves contained large numbers of cinerary urns made of alabaster or local tuff like a casket (APM01434). Volterra, Chiusi and Perugia were important urn production centres. The fronts of many caskets show a mythological theme. The Etruscans' familiarity with Greek mythology resulted from, among other things, their intensive contacts with the Greeks and their import of thousands and thousands of vases from Corinth and Athens. Smaller cinerary caskets were made of clay and furnished with a mould-stamped scene. A popular subject was the conflict between Eteocles and Polynices, the sons of king Oedipus of Thebes who were at one another's throats (APM01510). The stylized figure on the casket's lid represents the deceased. The figure typically leans on its left elbow and is rendered in strong foreshortening; curiously, a single anatomical detail is defined on the back: the feet.